Moorish Carpentry Alive Still

The art of Mudejar wooden ceilings, or techos de madera, is one of Spain’s most remarkable architectural legacies, a testament to the skill of master carpenters and the fusion of Christian and Islamic artistic traditions. These ceilings, found in palaces, churches, and civic buildings across the country, particularly in Toledo, Seville, Zaragoza, and Granada, display a breathtaking interplay of geometry, craftsmanship, and symbolism.

During the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, Spain’s Mudejar artisans, many of whom were of Muslim descent, adapted centuries-old techniques to embellish the grandest structures of their time. Their work was deeply influenced by Nasrid and Almohad decorative traditions, characterized by intricate interlacing patterns, elaborate coffered vaults, and the use of fine woods such as pine and cedar. Diego López de Arenas, a Sevillian carpenter and architect of the 16th century, codified many of these techniques in his seminal treatise, "Breve compendio de la carpintería de lo blanco y tratado de alarifes." His work laid the foundation for a new generation of craftsmen who would continue to refine Mudejar carpentry.

The term carpintería de lo blanco refers to a specific branch of Spanish carpentry that specialized in structural wooden frameworks, particularly for ceilings and roofs. The name "de lo blanco" derives from the color of freshly cut coniferous wood, such as pine, which was preferred for its strength and workability. This tradition dates back to the medieval period when wooden construction played a crucial role in architecture due to the limitations of materials available at the time. The geometría de lo blanco, as it was known among craftsmen, involved an intricate understanding of mathematical patterns that allowed for the assembly of elaborate wooden frameworks without the use of nails or adhesives. These designs, often adorned with interlocking lacería motifs, became defining elements of Mudejar craftsmanship.

One of the most stunning examples of Mudejar ceilings can be found in the Alcázar of Seville, where the master carpenter Francisco Rodríguez Cumplido created an extraordinary artesonado ceiling for the Hall of Ambassadors in the 14th century. This dazzling wooden dome, adorned with a complex honeycomb design, evokes the muqarnas found in Islamic architecture and demonstrates the seamless blending of Moorish and Castilian artistic influences.

In Toledo, the convent of San Clemente showcases another masterful example of Mudejar carpentry, attributed to Alí de Cárdenas, a renowned 15th-century craftsman. His work, visible in the cloisters and refectory, exhibits the typical laceríamotifs—intricate interwoven ribbons forming geometric star patterns—so characteristic of the Mudejar style. His influence extended beyond Toledo, as his workshop trained artisans who later worked on ceilings in Madrid and Segovia.

The Palacio de los Reyes Católicos in Granada stands as another landmark of Mudejar wooden artistry. The ceilings here, designed under the guidance of Enrique Egas, blend Islamic and Gothic motifs, mirroring the broader cultural synthesis that defined the city after the Reconquista. Egas, an architect known for his work on the Granada Cathedral, understood the value of integrating local craft traditions into the grand vision of Spain’s Catholic monarchs.

Beyond royal and religious commissions, Mudejar wooden ceilings adorned private residences and town halls. The Casa de Pilatos in Seville, a jewel of Andalusian architecture, features ceilings crafted by Hernán Ruiz the Younger, another master of wooden coffered structures. His ceilings, distinguished by finely carved beams and polychrome decorations, highlight the enduring appeal of Mudejar aesthetics well into the Renaissance.

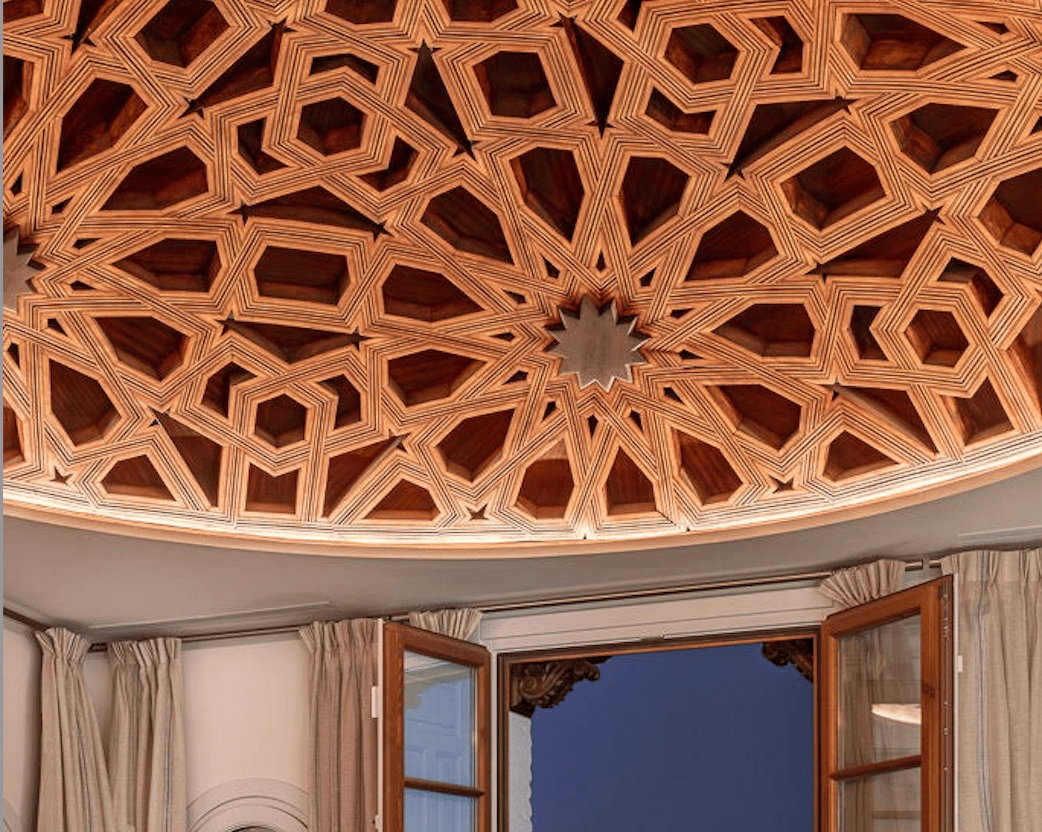

Today, the tradition of Mudejar carpentry continues thanks to artisans like Javier de Mingo, a contemporary master dedicated to preserving and restoring historical wooden ceilings. The image above taken from a carmen in Granada is a product of his creativity. His expertise in carpintería de lo blanco, together with that of his mentor Enrique Nuere and others such as , has allowed for the revival of intricate wooden frameworks that had nearly vanished over the centuries. His work, often seen in restoration projects across Spain, is a testament to the continued relevance of this ancient art form. De Mingo, along with other craftsmen, ensures that the techniques and knowledge of the past remain alive, adapting them to modern restoration and conservation efforts.

These wooden ceilings are more than mere decoration; they tell a story of artistic resilience, adaptation, and cultural exchange. As Spanish architecture evolved, the techniques pioneered by Mudejar carpenters were absorbed into the emerging styles of the Plateresque and Baroque periods, ensuring that the legacy of artisans like Rodríguez Cumplido, Alí de Cárdenas, López de Arenas, and modern-day figures like Javier de Mingo would endure in Spain’s architectural heritage. Even today, their ceilings remain a marvel—testaments to a time when craftsmanship transcended religious and cultural divisions, creating works of enduring beauty and complexity.